Maltese spend twice as much as EU average on healthcare

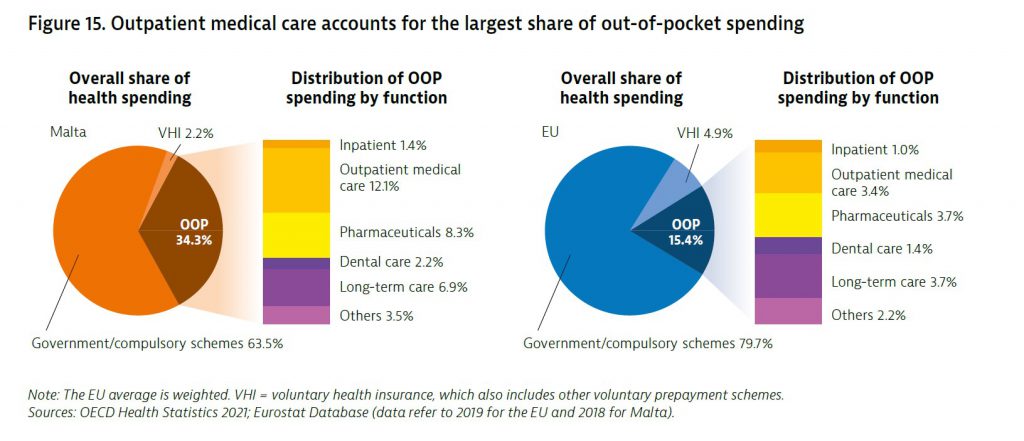

The Maltese are spending twice as much as the European average on private healthcare, despite having a free public health care service. It transpires that out-of-pocket spending (OOP) – the term used to described expenses incurred on treatment in private clinics and medicines – in Malta in 2018 was 34.3% of the entire share of health spending in the country which is the fourth highest proportion in the EU.

This data emerged from the State of Health in the EU Report issued by the European Commission which aims to give a snapshot of the health status of Member States including the effectiveness, accessibility and resilience of the health system.

Spending on outpatient care accounted for the largest share of OOP spending. This is driven by a substantial proportion of the population opting to purchase private primary and outpatient specialist care services, either for longstanding sociocultural reasons – Maltese people with a certain level of income and education have traditionally sought care from private practitioners. However, this is also due to the long waiting lists in State hospitals, whereas the same treatment can be received overnight in the private sector.

Out-of-pocket spending on pharmaceuticals and long-term care was also high. In 2018, OOP spending on health as a share of final household consumption was 5.5%, which is about 80% higher than the EU average of 3.1%.

Malta provides broad benefits, with public health care services and emergency dental care available free of charge to entitled individuals. Children under the age of 16, police and armed forces personnel and those on low incomes are also entitled to free elective dental services, prostheses, glasses and hearing aids. The rest of the population must pay out of pocket for elective dental care, which explains

Malta’s low share of public spending on dental care.

Medicines prescribed during hospital stays and the three days following discharge are available free of charge. Under the Pharmacy of Your Choice Scheme, people with certain chronic conditions are entitled to free medication related to that condition, while people with low income – as established by a means test – are entitled to receive certain medicines on the government formulary list free of charge. The Scheme covered approximately one third of Maltese residents in 2019. However, the majority of the population must pay for other prescribed pharmaceuticals out of pocket, contributing to a high share of pharmaceuticals being paid for from private sources.

Other key findings:

- Life expectancy in Malta fell by 0.3 years in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is below the average decline of 0.7 years recorded across the EU. Until early 2021, widespread testing linked to contact tracing alongside other public health measures contributed to Malta having a lower rate of infection than the EU average.

- Obesity rates among adults and adolescents in Malta are the highest in the EU. Recent legislation regulating advertising and food provision in schools, along with inter-sectoral investment to promote a culture of physical activity, aims to help tackle this major public health challenge.

- Life expectancy in Malta is high, but income-based disparities in health status persist. Strong public health policies contribute to low levels of preventable mortality, and deaths from treatable causes have declined substantially in recent decades as a result of improved health system performance.