Study exposes low spending power of low-paid workers in Malta

Malta’s minimum wage and low-paid workers scored low marks in terms of spending power in an EU comparative study, placing 16th out of 22 members states. Carried out by Eurofound, the study which has just been published, analysed minimum wages across the EU as at January 2022.

Apart from a straight forwarding comparison by ranking minimum wage values according to their respective values, the study looked at what is known as purchasing power standard (PSS). This term is used when seeking to make a comparison by factoring in the respective cost of living. Hence the PPS can be considered as an artificial currency measuring the price of a set number of goods and services which can be compared from a country to another.

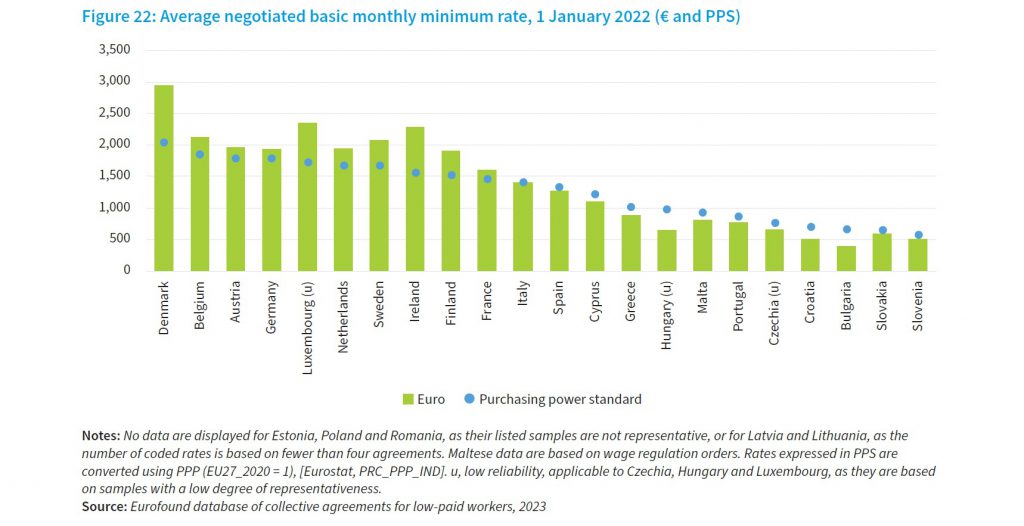

It transpires that in 11 countries the minimum wage was equal to or higher than the PPS. Denmark which had the highest minimum wage at €2,951 topped the list with a PPS of 2,042 followed by Belgium (1,850) and Austria (1,782). The other countries in descending order were Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Sweden, Ireland, Finland, France and Italy with the latter having its minimum wage practically equal to the PPS.

The 11 countries in the bottom half of the list had their minimum wage below the PPS. This means it even after considering Malta’s cost of living which is lower than that of the likes of Denmark, the minimum has nonetheless a weaker purchasing power. Malta ranked 16th having a minimum wage of €806 monthly but a PPS of 920. This value was based on wage regulation orders.

Among the countries with the lowest PPSs, equal to around a third of the PPSs of the countries with the highest values, are Slovenia (PPS 566), Slovakia (PPS 643), Bulgaria (PPS 663) and Croatia (PPS 698). For these countries, the figures indicate that the sampled collective agreements are (at least partially) outdated, as they are below the statutory minimum wage.

From a wider perspective, the report concluded that even though collective bargaining could be a vehicle for avoiding unduly low-paid labour, it might not always be sufficient. Findings from this project show that collective agreements in certain countries do not always contain pay rates, and that pay rates frequently fall behind the statutory minimum wage. This can be ‘by design’, for example because industry agreements do not specify minimum wage levels (as observed in Sweden), leaving actual pay-setting to take place at different levels. However, it could also be indicative of a more limited role given to pay regulation in collective agreements.

In more modern types of agreements, pay is not differentiated based on occupation or seniority but is linked to job demands in terms of skills, autonomy and responsibilities. While the differentiation of pay in agreements did not change much over the observed period, the project has shown that in a few countries and agreements such change is ongoing. Seniority and professions, nevertheless, remain the most widely used differentiators for collectively agreed pay.

The fact that in some Member States many collective agreements are outdated highlights the role and importance of promoting and reinforcing collective agreements in pay-setting. In this context, statutory minimum wages have a key role to play in effectively protecting workers from unduly low pay in countries and sectors with a low collective bargaining rate and a low degree of organisation.

In contrast to statutory minimum wages, which in the EU context usually provide one wage floor, collective agreements can also regulate the pay of medium-and higher-paid workers. However, this opportunity is not always taken and could be expanded in some countries and sectors.